In 2020, like many other people, I sat at home and needed to figure out a way to kill time. The Criterion Channel launched not too long before the world shut down, which gave me an escape to look into some otherwise unknown films. I am, without a doubt, a complete sucker for Criterion films - partially because of the incredible restoration of some amazing films I never had direct access to, but mainly because of their incredible packaging. So, after seeing so much about this Three Colors Trilogy, I watched some behind the scenes extras the channel had to offer and dove right in.

At first I’d be remiss to say that three artsy French films sounded like they’d be a slog. However none are over 98 minutes and, more importantly, I’m a sucker for an intertwined series. Yes, multiversal storytelling has become tiresome in the age (and post-age) of the superhero, but I love a good easter egg that confirms that things live in the same universe (be it some author’s work or The Legend of Zelda series). Needless to say, after watching all three of Kieślowski’s works, I was enraptured - even if I didn’t know how to properly pronounce his name. Each film was so wildly different in style and tone, and yet all were made of the same DNA. This man was a true master and I needed to read and watch every piece of critique and thought about them.

The Three Colors Trilogy was a concept Kieślowski came up with after his highly successful Decalogue series and The Double Life of Veronique. He wanted to take the concept of the French tricolour - the blue, white, and red from the flag that represents liberty, equality, and fraternity respectively - and explore its three symbolic themes in three interconnected films that could also stand alone in a post Cold War Europe. As he discovered along with his writing partner Krzysztof Piesiewicz, what they wanted to explore was not what they ended up realizing. And thus, we have three films that explore a variation of these ideas alongside the color motifs they each represent.

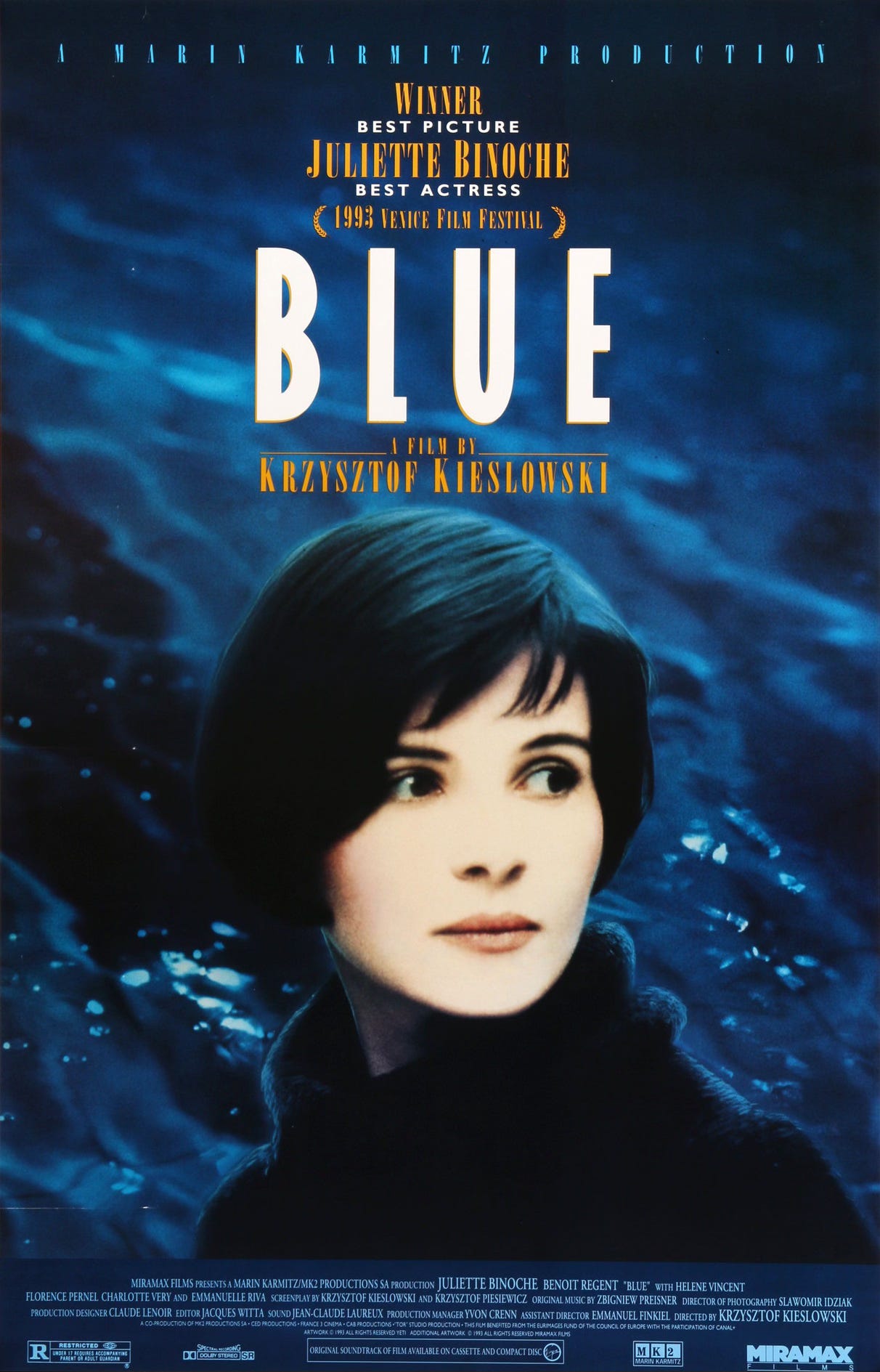

Three Colors: Blue was the first set in this trilogy and would go on to be entered in and win Venice. The film follows Julie (Juliette Binoche) as she deals with the aftermath of losing her daughter and world class composer husband (of which she secretly aided in creating his compositions) in a car crash in the opening scene. This first film is supposed to explore the idea of liberty and what that could mean in a situation where love is such a dominant and unshakable force; paired with the color blue - a color we commonly associate with sadness and depression - it is easy to accent Julie’s journey throughout this film.

Whenever we are in Julie’s world - whether she’s by herself or we are living in her POV - the cool colors flood the screen in some way shape or form. Slawomir Idziak’s cinematography in this film utilizes a lot of filters to help punctuate this notion, as do various items we associate with blue, like water. Whether it is being caught in the rain, or swimming alone in the pool, Julie is constantly trying to wash herself clean of this past and her feelings, so much so that she attempts to sell her entire estate and start completely anew.

However, even this seems to be impossible. Even when she attempts to sell off her house, all of her possessions, and live only off the money she has in her account, she has one keepsake that keeps her tethered to her past life - her daughter's blue glass chandelier. Even with all the new furniture and stylings in her place, this one thing keeps her attached to a past she wants to liberate herself from.

But what is there to do? These permanent feelings of unconditional love are inherently impossible to escape, because once they are embedded in you, they are there forever. At first when she goes to visit her mother who is suffering from dementia, it seems as if she is almost jealous of her mother’s disease, to be removed and have no memory of a past life1. She comes to realize later that love is in fact so strong, that even when your brain is rotting from the inside out, the only memories you have left are of loved ones, even if they are imperfect.

Julie is trapped by these feelings, unable to break free from the emotional cage she feels imprisoned in. We are again shown this throughout the film by the amount of glass and screens used as a barrier between her and the world surrounding her. It could be watching her family’s funeral on a small television, watching her husband’s mistress through a window in a restaurant, or learning of her husband’s mistress through a TV through a manager’s window (double screen) in a sex club. She may make attempts to break free from her enclosure, such as shattering a window in the opening hospital scene, but she is forever encased by these emotions.

The way we view Julie is almost animalistic behind these panes of glass. In the beginning after her failed suicide attempt, she looks up to see a nurse watching her on the otherside of the window, like she is observing an animal in a zoo. It might be better to compare her more to a fish in a tank2 the way we view her swimming in the pool or how her sex scene with Olivier is shot. Julie is shown pressed against glass framed by various looking aquatic weeds and kelp as she seemingly uncomfortably has sex, as if to feel something inside of this arena.

This point of view for the viewer allows us to have the voyeuristic tendency that many do with real world situations. If we see things behind a screen - be it digital or real - there is a physical barrier between us and the subject, thus removing ourselves from the entire situation. We may see people struggling daily in wars and conflicts around the world, even right outside our own homes, but that physical barrier of separation removes us from the situation as a whole. Julie comes to realize this during her stalking of the mistress, knowing that this distance and separation is providing her safety as she keeps tempting the fates by getting closer and closer to an emotionally dangerous situation. The times she breaks this - helping the sex worker downstairs, approaching the mistress, addressing the street performer - are when the shades of blue from her world are lifted.

It is only then, when Julie realizes that shelling herself off from these emotions will not liberate her depression and despair, but is instead exacerbating them. The only way to true freedom is to accept what has happened and live through loved ones with what they have left us. That could be a piece of composed music that will be played for a united Europe or a child, but no matter what we do, there is always going to be something somewhere that keeps us tethered to those we love. And once we accept that, we can break out of our cages and finally stop being blue.

Again, punctuated by how her mother is watching bungee jumping and tightrope walking on the television when she visits her. Julie is almost scoffing at these people who want to chance death yet keep them tethered to real life. For if they truly wanted to try to die, they would not have their cables and poles and just do it.

Along with the motif of water, specifically rain, invoking both the idea of dreariness and cleansing.